My current international film projects differ greatly from one another. Broken Desert is a demanding thriller—the complete opposite of Bright Day. Its development requires close international collaboration in the UK and the United States. For the first time, I am also relying on agents in this process.

What inspired you to become a filmmaker, and how did your journey in the film industry begin?

I grew up in the former GDR (East Germany). At the age of 16, in 1980, I made three amateur films (16 mm). One was a documentary titled “Am I Lonely?” about a victim of Nazi persecution who spent her final days in a nursing home. At the end of the film, she mentions that she fought for a better society her entire life and that she cannot understand why young people in the GDR no longer feel any love for their country.

My second amateur film, “In the Cellar,” a short film (16 mm), was made in 1985 and was based on a play by the then highly critical and internationally renowned playwright Heiner Müller, who granted me permission to use his work. I made this short film with well-known GDR actors.

My third amateur film, “When You Transplant Old Trees,” tells the tragic story, in documentary form, of two men who lost their homes due to open-pit lignite mining in the GDR.

Those were my first encounters with the medium of film—and they had consequences. When I applied to study directing at the Konrad Wolf Film University in 1986, I successfully passed the two-week entrance exam. When I later stood before the admissions committee of the HFF, which consisted of professors from the university, representatives of state television and the DEFA film studio, as well as representatives of the SED (the ruling party), these three amateur films proved to be my downfall because of their political statements, as I later learned.

It is important to note that at that time, only six students were allowed to study film directing every two years. In addition to artistic talent, in those difficult times, a formal recommendation from GDR television and the DEFA film studio, as well as membership in the ruling SED party, were mandatory. I could not—and did not want to—provide any of that.

Then, in 1988, I received a telegram from the new rector of the HFF, Lothar Bisky, informing me that I was now allowed to study. This was made possible by the East German television directors Richard Engel and Wolf-Dieter Panse. I appeared before the same commission that had rejected me years earlier, and this time I was admitted. Mikhail Gorbachev, Glasnost, and a few courageous people made it possible. Thus began my journey into the film industry.

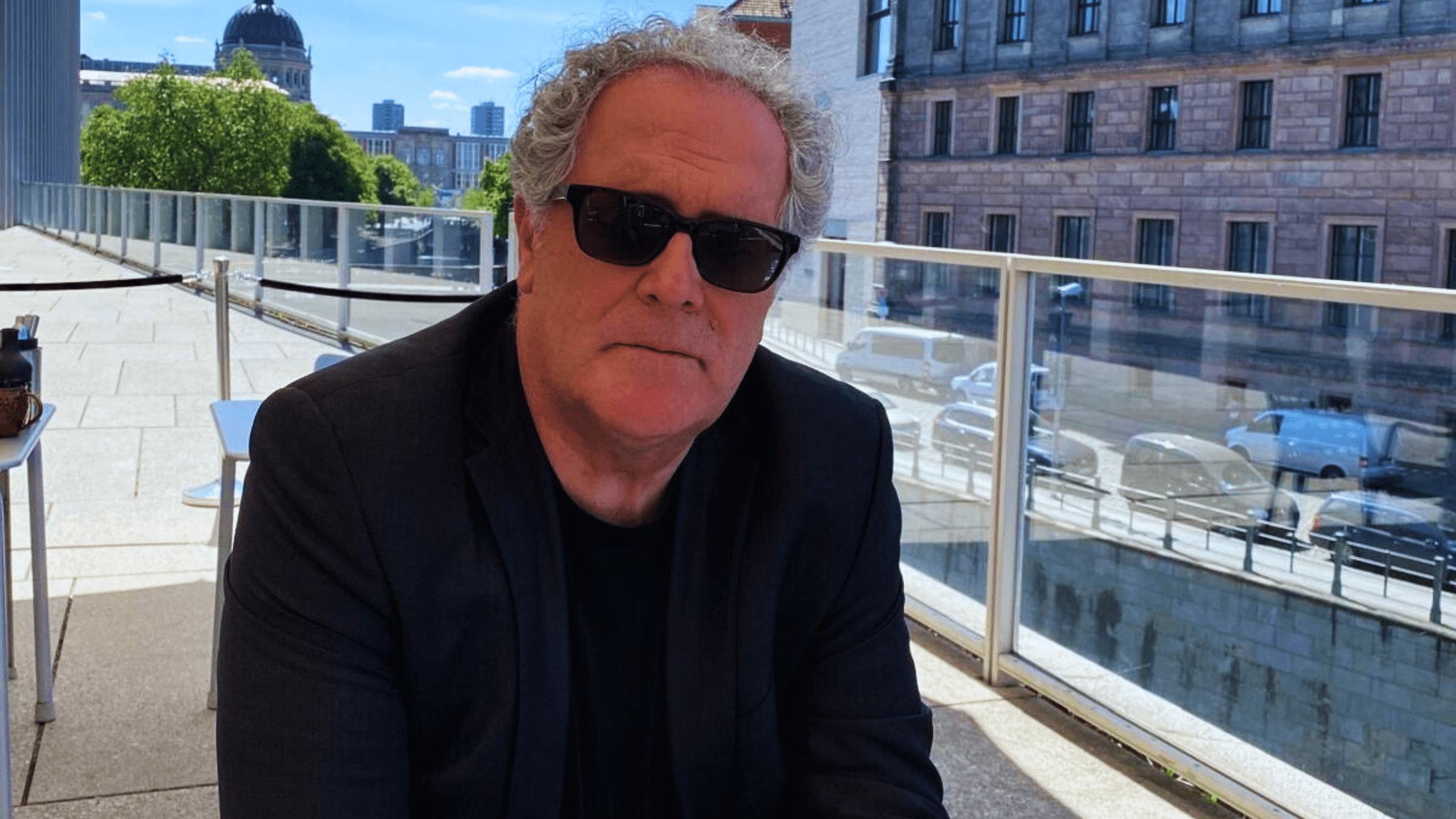

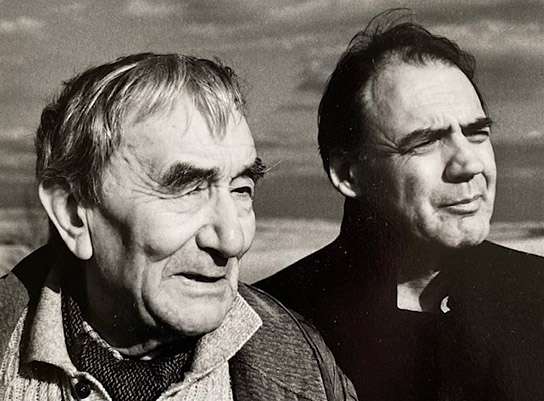

My first truly pivotal encounter with film was a walk with Bruno Ganz in Berlin-Pankow (East Berlin, 1993). He had read our script and wanted to meet me. We walked for hours, and he agreed to take on the lead role. Before that walk, the film had already been financed with a minimal budget. Bruno confided in me, and I confided in him. When he saw the finished film, he hugged me—and I hugged him. Thank you, Bruno. That was my debut—my first real encounter with film.

Can you share a specific moment or film that significantly influenced your creative vision?

Back then, it was definitely the films of Ingmar Bergmann and Andrei Tarkovky that influenced me most. At the time, I wrote my diploma thesis in directing on the subject of faith in film.

What is your typical process for developing a film project from concept to execution?

This cannot be generalized. At this point in the interview, I would like to mention that even back then, I had decided to develop and realize only a limited number of my own film projects.

In 1994, I focused on several major feature film projects. These included the thriller “Two Up” (The Book), the arthouse film “The Sheen of Night,” the second part of “Bright Day,” and the thriller “Broken Desert.”

In 1995, immediately after “Bright Day,” we received project development funding from European Script Fund London and producer funding from ACE Producers Paris for the thriller “Two Up.” This was an international honor for Gabi Blauert and me. I then continued to develop the project over several years.

I mention the project’s development history here so that independent filmmakers at the beginning of their careers can understand what project development can mean—and what consequences it can have.

1997 – Script and project development with European Script London and ACE Paris; numerous meetings with the renowned British actor Alan Rickman.

1997 – 20th Century Fox (USA), Bob Aaronson (VP Acquisition and Production):

“After reading the script, Mr. Aaronson was very interested in international distribution, sales, and a possible coproduction (for Fox Searchlight).”

Bob Aaronson:

“No problem with Andrey Nitzschke as director after seeing his film ‘Bright Day,’ starring Bruno Ganz.”

1997 – Miramax (USA), Jennifer Burman (Creative Director): After reading the script, she expressed strong interest in international distribution.

1997 – New Line Cinema (USA), Paul Federbush: Due to the strong concept, compelling story, and high-quality script, they requested updates on further developments and expressed interest in end distribution.

1998 – Japanese producer Shoko Kimizuka (“Smoke”): She liked the story very much but was unable to access the project without a main producer.

Producer Wieland Schulz-Keil—who had worked with John Huston, Peter Bogdanovich, Roger Spottiswoode, Anthony Hopkins, Alan Rickman, and Arthur Cohen—was very interested in producing the film. Unfortunately, negotiations between his agency and the authors’ agency regarding the script contracts failed, and the collaboration ended. I was deeply saddened by this, as it had been my wish to work with him.

Ultimately, another German producer secured the contract—an outcome that proved to be a momentous mistake. We lost the rights to the material for 28 years. After signing the script and directing contracts, the producers informed us that they intended to realize the film with different, well-known authors and another renowned director. We did not agree. The consequences were serious.

Only this year, together with the agency, were we able to transfer the rights back. Now, 28 years later, I am once again exploring potential producers in England. This illustrates what filmmaking can entail.

I would now like to briefly mention other future projects.

“The Sheen of Night” is an arthouse film and the second part of “Bright Day.” The story is set primarily in refugee camps in Greece and Sri Lanka. Originally, the film was intended to be set in India, but due to the high production costs there—and based on my positive experiences in Sri Lanka—I revised the material and relocated the story. Like “Bright Day,” “The Sheen of Night” is an arthouse film about a great love and about farewell.

“Broken Desert” is a challenging commercial thriller project. I presented it to Paramount Pictures (USA) in 2017, where it was received with interest. However, a change in studio management prevented further development at that time. I am currently in talks with various producers in England and the United States.

Alan Rickman—who supported my plans extensively—was interested in the lead role. I had come to know him well through the “Two Up” project, and he remained interested in this role for a long time. Then he passed away.

Finally, I would like to mention that in 2024, I developed a two-part international documentary film that will be funded by sponsors. The working title is “The Secret.” The film tells the story of the extraordinary work of Gerhard F. Klügl, a well-known alternative medicine practitioner in Europe, who has developed a system of subtle, bloodless surgery and collaborates with orthopedists, surgeons, dentists, and other medical professionals across Europe.

Gerhard F. Klügl also supported me personally with his method. This will be an extraordinary film. An independent distributor in the United States will handle worldwide distribution.

All of these projects are now ready for further development, financing, and release.

How do you approach storytelling in your films, and what themes do you often explore?

As I mentioned earlier, I develop and realize only my own projects. This often requires a great deal of patience and sensitivity. Because my films consistently deal with deeply existential themes, my experiences over the past decades are proving invaluable today.

My current international film projects differ greatly from one another. Broken Desert is a demanding thriller—the complete opposite of Bright Day. Its development requires close international collaboration in the UK and the United States. For the first time, I am also relying on agents in this process.

The follow-up project to “Bright Day” is a European arthouse film. I am currently considering whether to produce it myself or which producer would truly be capable of realizing such an arthouse project set in Sri Lanka. Without European film funding—specifically cultural film funding—this film cannot be financed.

Jens Harzer would love to take on the lead role. Years ago, he received the Iffland Ring from Bruno Ganz, one of the most prestigious honors for actors in European theatre.

I would like to emphasize that I do not allow time pressure to dictate the development and financing of my few projects. I can take my time. At various intervals, I serve as the lead coordinator in international medical and humanitarian crisis intervention in crisis zones around the world—and the situation there is intensifying. Film is not everything.

Of course, art—including film—is essential for all of us. It nourishes the mind and the soul in one way or another. However, I have never been a fan of red carpets, non-committal meetings, or self-importance in the film industry. Unfortunately, film development is often marked by exactly these traits. And honesty? No comment.

What are some of the biggest challenges you face as an independent filmmaker?

Dishonesty, fraud, greed, selfishness, breaches of contract, social and psychological insecurity, and much more.

Can you share an experience that taught you a valuable lesson in filmmaking?

I would also like to refer to my answer to Question 2.

How do you select your collaborators, such as writers, actors, and crew members?

Filmmaking is teamwork. Respect and appreciation for the work of drivers, lighting technicians, and all other crafts are fundamental to the creation of a film. I used to work consistently with the same teams. Nowadays, with large-scale projects such as Broken Desert, I have far less influence over the individual departments. Even so, the same principle applies: respect, high regard, and sensitivity.

The situation is different with arthouse films. Here, I try to work with people I trust. I approach actors for the arthouse project directly myself. For the commercial film “Broken Desert,” I often cast actors intuitively, sometimes contacting them personally or—only as a last resort—leaving the communication to international agencies when personal progress is no longer possible. Almost all of this requires time and patience.

I developed the screenplays together with my screenwriters, Gabi Blauert and Jörg Weismann. For Broken Desert and Two Up, I will also involve experienced writers from the UK and the United States.

What role do you believe collaboration plays in the filmmaking process?

Collaboration is the foundation of filmmaking—without ifs, ands, or buts.

How do you connect with your audience, and what do you hope they take away from your films?

If I am contacted personally, I will respond personally. Otherwise, the films must speak for themselves. I do not want to explain my motivation or vision to the audience.

When I was in Tokyo and the United States, the conversations with viewers were often very long and specific. I was happy to engage—regardless of whether the feedback was positive or negative.

Therefore, I probably cannot answer your question to your full satisfaction.

What strategies do you use to market your films as an independent filmmaker?

The distribution of a film is important for the producer, the creative team, and the audience. This aspect must be carefully considered from the very beginning of project development, starting with the existing screenplay.

Every film has its own strategy. In these times of upheaval, planned strategies are often short-lived and, in my view, not always successful. Personal relationships based on competence and trust guide my work. Because I make only a few films, I am not under pressure to produce constantly or to prove my success at any cost.

The internet and social media are very helpful in my work, even though I do not have Facebook or other social media accounts. Once the right producers and distribution partners are found, things begin to move forward; sometimes, however, progress is halted by financing issues. Eventually, though, momentum returns.

What do you think are the biggest changes in the film industry for independent filmmakers in recent years?

The societal, intercultural, and social tensions and changes of our world. Cinema is slowly losing its significance—and there are reasons for this. Many people are increasingly unable or unwilling to experience films in cinemas. Despite this, the film industry continues to celebrate itself. I can observe this clearly in Germany.

Appearances are deceiving fewer and fewer people. Many stories resonate less emotionally. Retreating to the living room with Netflix and similar services is convenient—and cheaper.

Almost all the producers I know collaborate with these streaming platforms, often producing large amounts of uninteresting content. Just as in the past with cinema, people who no longer go to movie theaters are now being served similar content—by many of the same people who once made often unremarkable films for the big screen.

Netflix once distinguished itself by streaming highly interesting films—and now… what a shame.

How do you feel about the rise of streaming platforms in relation to independent cinema?

There is no independent cinema anymore. Did it ever truly exist? Unfortunately, I never benefited from it. Netflix — which I once considered a highly interesting addition to cinema—also does not allow for genuinely independent film distribution. At least on Netflix in Germany, I have watched almost nothing, apart from a few exceptions such as Dark.

What projects are you currently working on, and what can audiences expect from you in the future?

As I explained in Question 2, there are two international thrillers, Broken Desert and Two Up. They are the complete opposite of Bright Day. Previous letters of intent for the cast included Alan Rickman and Bruno Ganz. That should speak for itself.

In addition, there is the arthouse film When My World Ends, the follow-up to “Bright Day,” as well as the international documentary The Secret. The latter is a very personal film about Gerhard F. Klügl, who works with medical practitioners across Europe using a subtle energy method.

Are there any particular genres or styles you wish to explore in your upcoming films?

As mentioned, André Nitzschke will be making completely different films: a psychological thriller and a socio-political thriller, as well as a film similar to Heller Tag — a poetic parable.

Looking back on your career, what advice would you give to aspiring independent filmmakers?

I already mentioned this in the interview I gave about India in 2025, and I would like to repeat it here:

My advice: Never give up. If film has irrevocably captivated you as a creative medium, be aware that storytelling is sometimes a long marathon. Some filmmakers reach the finish line early, others much later—or not at all. However, there are no defeats. There are only experiences, both good and bad.

Film is not everything in life. But my advice remains the same: Never give up.

Links Andre Nitzschke

https://www.filmportal.de/film/heller-tag_8bed2dbe00e64481a7f91b6cfb9405e6

https://www.imdb.com/de/title/tt0110011/

linkedin.com/in/a-nitzschke-153110144

Awards Bright Day

International Independent Filmfestival Kalifornien 2025

- International Independent Film Awards Californien USA, Best Director

- International Independent Film Awards Californien USA, Best Actor

Peshawar International Filmfestival Pakistan 2025

- Best Actor

Bangkok Movie Awards 2025

- Bangkok Movie Awards, Best Film Religion

- Bangkok Movie Awards, Bester Actor

Bangkok Society of Film CRITICS AWARD 2025

- Bangkok Society of Film CRITICS AWARD, Best Director

Indian Independent Filmfestival 2025

- Best International Film

- Beste Director

- Bester Darsteller

Sweden Film Awards 2025

- Sweden Film Awards, Best Actor

Chicago Filmfestival 1994

- Nominierung, Bester Film